The Remarkable and Misunderstood Life of Lucrezia Borgia

This article concludes our series on the infamous Borgia family—one of the most controversial dynasties in European history. Today, we turn to the woman who became both a symbol of Renaissance brilliance and a target of centuries-old rumors: Lucrezia Borgia.

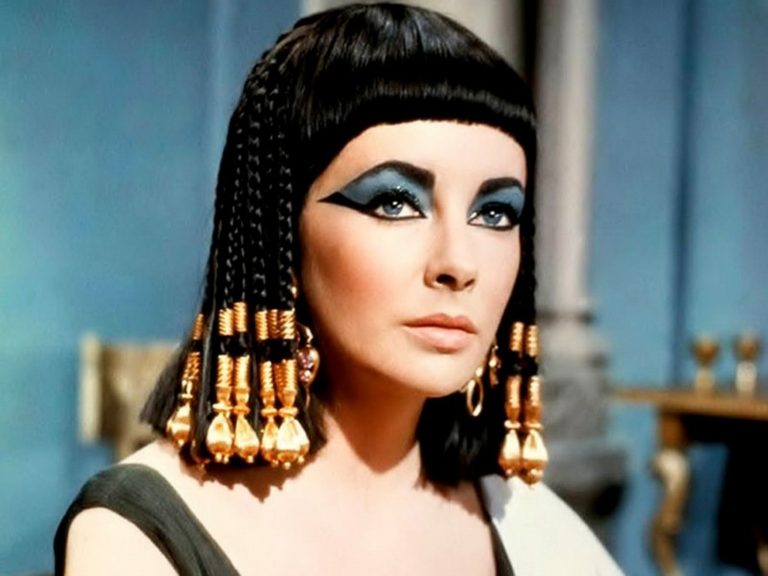

A Woman of Beauty and Extraordinary Intelligence

Lucrezia Borgia (1480–1519) was widely regarded as one of the most beautiful women in Italy. One contemporary wrote admiringly: “Her mouth is rather large, her teeth dazzling white, her neck slender and fair, and her bosom beautifully shaped.”

But beauty was only part of her story. What truly set Lucrezia apart was her education—something rarely afforded to women of the 15th century. Under the guidance of her father’s cousin Adriana Orsini, she studied Latin, Greek, Italian, and French. Whenever Pope Alexander VI encountered a new scholar, he ensured that Lucrezia learned from them.

At a time when most girls were taught little more than religious basics by convent tutors, Lucrezia’s intellectual upbringing was exceptional.

A First Marriage Erased from the Record

When Lucrezia was just 13, Europe’s noble families competed for the chance to marry into the papal household. Pope Alexander VI ultimately chose Giovanni Sforza in 1493 to strengthen political ties.

But when the Sforza family allied with France—against the pope—Giovanni became a liability. Forced to flee Rome, he narrowly escaped assassination. The Borgias then demanded he publicly confess impotence so the marriage could be annulled on the grounds it had never been consummated.

Humiliated, Giovanni complied. Lucrezia was legally restored to “virginal” status, once again a highly desirable political bride.

Her Second Husband Likely Fell Victim to Cesare Borgia

At 18, Lucrezia married again—this time to Alfonso of Aragon, the illegitimate son of the King of Naples. At first, he seemed a perfect ally. But political tides shifted quickly: Cesare Borgia accepted French support, abandoned his cardinalship, and allied himself with France against Naples.

Suddenly, Alfonso became an obstacle.

Lucrezia warned him of the danger, but in 1500 assassins ambushed him after a dinner at the Vatican. Wounded but alive, he sought refuge. Cesare finished the job soon after.

Lucrezia was devastated.

The Unusual Governor of Spoleto

Lucrezia’s education and years spent shadowing her father gave her a sharp instinct for politics. Whenever Pope Alexander VI left Rome, he often entrusted her with oversight of the Vatican—an astonishing role for a woman of that era.

In 1499, after Alfonso had fled Rome, Alexander appointed Lucrezia governor of Spoleto, a position typically reserved for male nobles. She ruled effectively even while pregnant. Her competence, however, also fueled rumors—powerful women always made easy targets.

A Third Marriage and a Web of Affairs

Lucrezia mourned deeply after Alfonso’s death, signing her letters La Infelicissima—“the most unhappy woman.” But political ambition never rested in the Borgia household, and in 1501 she was married off again, this time to Alfonso d’Este, heir to the Duke of Ferrara.

Their union was strategic, strengthening ties in northern Italy where Cesare was expanding his territories. Lucrezia bore Alfonso eight children. Yet her life in Ferrara was far from quiet: she had several famous lovers, including the poet Pietro Bembo and the celebrated knight Chevalier de Bayard.

A Scandalous Affair with Her Brother-in-Law

Lucrezia’s most infamous relationship was with Francesco II Gonzaga, the Marquis of Mantua—and her brother-in-law. He was married to Isabella d’Este, Alfonso’s sister, and Isabella and Lucrezia already disliked each other.

Francesco’s affair with Lucrezia enraged his wife and fueled regional gossip. He also suffered from syphilis, though Lucrezia appears not to have contracted it.

The Poisonous Legends

History remembers Lucrezia as a seductive killer who used poison to remove her enemies. For centuries, stories circulated of rings with hidden compartments and wine cups secretly laced with toxins. But historical evidence for any of this is nonexistent.

These tales likely grew from:

-

Her close association with Cesare, who truly was ruthless

-

Her unmistakable political talent

-

Misogynistic assumptions that a powerful woman must be dangerous

Rumors of incest only added fuel to the fire. Yet when evidence is examined, the claims collapse. Even the story that the Borgias accidentally poisoned themselves—after a banquet where both Cesare and Alexander VI fell ill—is probably a myth. Alexander’s death was almost certainly caused by malaria, not mismanaged toxins.

A Beloved Duchess in Her Own Lifetime

Despite the dark legends, Lucrezia became a respected and admired ruler. When Alfonso d’Este inherited Ferrara in 1505, Lucrezia flourished as duchess. Her court became a vibrant cultural center, buzzing with musicians, scholars, and poets.

She organized tournaments, patronized artists, and governed with compassion. The people of Ferrara adored her, praising both her beauty and her “grace of character.”

A Life Cut Short at 39

Tragedy surrounded Lucrezia in her final years. By 1518, her parents, her brothers and sisters, her eldest son Giovanni, and her lover Francesco had all died.

Her own health declined. Pregnant again at 39, she gave birth prematurely to a daughter who lived only a few hours. Lucrezia died nine days later, on June 24, 1519.

Her husband Alfonso fainted at her funeral. He lived another 15 years and was buried beside her in 1534.

The Downfall of the Borgias

Without the protection of Pope Alexander VI, the Borgias quickly lost their power. Lucrezia’s marriage into the Este family shielded her from enemies, but later generations had no such defense. Wealthy but politically diminished, the once-fearsome dynasty faded away. By the mid-18th century, the Borgias had disappeared entirely.

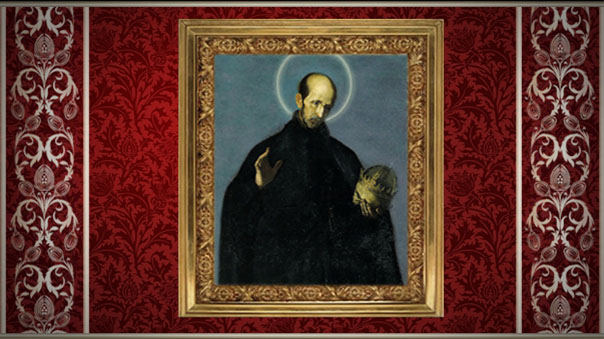

The Borgia Saint: Francis Borgia

One descendant, however, redeemed the family name. Francis Borgia (1510–1572), great-grandson of Alexander VI, turned away from nobility to join the Jesuits. He became a missionary, founded colleges in Spain, helped establish a university in Rome, and was canonized in 1670 after numerous reported miracles. To Catholics, he represents the spiritual renewal of a family known for corruption.

A Legacy That Shaped Culture for Centuries

After Lucrezia’s death, Borgia legends spread rapidly. Machiavelli immortalized Cesare in The Prince. Dramas, novels, and operas followed—Victor Hugo’s Lucrezia Borgia and Donizetti’s opera among them. The 20th and 21st centuries brought films, novels, and television series that cemented the sensational image of the Borgias in popular imagination.

Whether portrayed as villains or tragic heroes, the Borgias continue to fascinate us—proof that history’s most controversial families rarely fade quietly.